A few years ago, I picked up the Lego Architecture Studio on Amazon and have not been able to play with it as much as I wanted to – it was an indulgence in simply having legos in the new place because I grew up with them, collected into an old pickle bucket my mother had found. In reorganizing, I rediscovered them within the dusty box, and the book that came with it.

A few years ago, I picked up the Lego Architecture Studio on Amazon and have not been able to play with it as much as I wanted to – it was an indulgence in simply having legos in the new place because I grew up with them, collected into an old pickle bucket my mother had found. In reorganizing, I rediscovered them within the dusty box, and the book that came with it.

One of the things I had been noticing over the decades is how the Legos of my childhood have made way for all sorts of specialized Lego sets. There were less specialized sets when I was growing up, and in an odd way, I found more space for imagination because of it. I recall spending a lot of time creating spacecraft that had engines, and of course weaponry because I had grown up in the era of Star Trek and Star Wars. I couldn’t talk too much or be seen playing with them in that way because at the time, we were Jehovah’s Witnesses, and anything that went pew was forbidden. But I built them anyway, and convinced my mothers that the weaponry were headlights when she asked because, “Space is dark”.

There were other toys, like Capsela and Tinker Toys. For now, the Legos.

Legos allowed me to organize, build and imagine. I was left to my own devices with them. It was a framework I could build from, the then proprietary blocks allowing me to build what was suggested – and to create my own imaginary things. The new more specialized systems with their little special parts would allow more of that, but all within what the Lego framework allows to be possible.

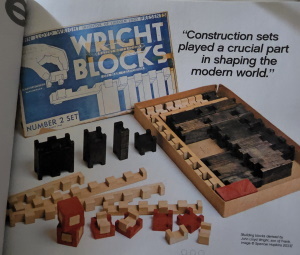

When I looked in the book, it mentioned things in line with the things I am writing about in more of a long form. What we play with defines how we shape our worlds. We start with objects as children, connecting them together in ways through experimentation to build things. Sometimes we imagine them in advance. Sometimes we just want to see what happens. Sometimes we have no idea what we’re building until we are done – and sometimes we are never done.

This is what we do. Douglas Adams went further back, jokingly maybe, writing of ‘twig technology’. We started off with sticks and stones, poking and bashing things, creating tools that we then built further with to the complexity that we now have specialized tools that are put into stores which are full of such potential. We place them in stores, their smell of plastic and metal permeating the hardware, their marketing so good that we buy things on average that we rarely use, like electric drills.

All of these things give us biases in how we see the world. What we use defines how we see the world, just as what we observe does the same.

This, though, is only the realm of the physical world. We do the same with abstractions, and that’s where it really gets interesting.

We build with what we have, and we are biased based on how we are influenced. Yet, too, we are also limited by what we have and how our biases influence how we look upon them. It’s only when we understand that, when we can work beyond those biases and maximize what we have available on hand that we truly move forward.

Tomorrow, I’ll dive into the abstractions.

2 thoughts on “A World Built, Part I.”