There’s a lot to consider these days regarding intelligence and consciousness. I’ve developed my own thoughts over time, as we all have to some degree, but few of us it seems have the time or inclination to really sit and think about such things.

What separates us from other forms of life on the planet? Only we have excised ourselves from the rest of life on the planet as far as we know, and that’s fairly narcissistic of our species, a species where we accuse individuals of our species of narcissism – which must mean that they’re pretty bad if they merit a diagnosis rather than suffer armchair psychologists around the world.

When we boil down what reality is for us, it’s all derived from our senses. We look, we smell, we touch and we listen – these are our inputs, and from it we develop a model of the world within what we call our minds, which we blame our brains for. Yet there are other senses we have related to our own bodies and how we physically and emotionally feel at any given time, and influences how we perceive the world.

How that interacts with others is akin, if not the same thing, as a ‘sphere of influence’ – something my father often talked about, since he had heard about spheres of influence somewhere: I’d read all the same books he had, sometimes even before he got finished reading them. I don’t know where he was introduced to the concept, but the concept is worth fleshing out in an era where we’re all data streams to fund some billionaire’s stab at a version of success that seems disassociated with the rest of the planet.

It is always fashionable to point out others live in bubbles, and saying that billionaires live in bubbles doesn’t let us off the hook. Some people admire the bubbles and want to get into a bubble – a sphere with that much influence.

I’ve been listening to Lex Fridman podcasts on YouTube in the background off and on over the past month, and I forget in which of them he mentioned that he wanted to use his influence for good in an election year, or in some other thing, and I admired his honesty in that and worried that his own sphere wasn’t broad enough to truly have an effect I would desire. Often he seems a supportive role in whomsoever he talks to. I forced myself to listen to his episode with Elon Musk – at least one of them, they seem to talk offline a lot – and in that podcast there seemed a lot of soft pitches to Musk, and much of it was nothing more than what I call an advertorial.

To his credit, the casual listener may not have picked up on that with Musk, and those who want to be like Musk (in whatever way) wouldn’t want to notice it, but as someone who is not impressed with Musk, I forced myself to listen to the interview and be as objective as possible. Musk, like everyone else, wants to make the world a better place, but the way that he sees the world is often incompatible with reality in my mind. That being said, I listened and found myself mildly impressed with how human he came across. Yet when I thought through everything, it was a mildly entertaining soft pitch for Grok throughout, while not actually challenging Musk.

The comments on the video were quite supportive of Musk. It’s a hit. Lex Fridman, then, would see how many views the episode had, read the comments, and think it was all wonderful – but having listened to many of these sessions, and watching the body language in the videos, some of those interviewed (and I include Musk) weren’t really challenged and where criticism of them was either ignored or simply peacefully bridged, as if the opinions didn’t matter.

And yet, there were gems, like this one with Sara Walker. It’s long, it’s worth it, and while she does seem to have what I call a ‘Valley Girl vocal tic’ which I generally don’t find endearing and often have trouble taking seriously. ‘Fer shure!’ and stuff like that have been grossly overdone with shallow movies, and isn’t something I hear often outside of that context – but she is amazingly well thought, and like me, she likes playing with words (and also like me, apparently, doesn’t think in words).

It was a soft pitch for her upcoming book, too, but in this context – and I’ll give Musk credit for saying this, paraphrased – advertising that is contextual to what a person wants or needs at a time is content. Well, maybe, it depends on how the want or need was created. It happens that she was talking about things that I was thinking about and she randomly popped up in YouTube. If you’re interested in that sort of thing, watch the video. She’s quite well thought on all of this. She’s someone I wouldn’t mind having coffee with, if she could put up with my speaking style – I imagine it works both ways. Regardless of how Sara Walker says it, she says a lot worth listening to1.

When ideas collide in the ether between we humans, it’s because of language communicating a common concept between people. It can be between two people, and that develops a common language. It can happen within a group of people who work or play with the same things, which gives us lingos. On rare occasions, these lingos – words or acronyms – can go mainstream, as the meme about memes did by Richard Dawkins. And even then they can be curtailed by languages2, and when it transcends language, it hits very mainstream.

This all fits really well with the concepts that Pierre Levy has communicate in his own way over the decades brilliantly. Being more steeped in being multilingual than I, reading his works was at first challenging.

One of the beautiful things that Levy writes on is IEML, a semantic language he created that has challenged me more than I have had the capacity to challenge it. I have yet to see someone come up with an equivalency, which may exist. I have also yet to see anyone approach a lot of knowledge management in the same regard, particularly in an age where Large Language Models are also ‘Literal Language Models’.

These spheres of influence are telling. Pierre Levy resides mainly in academia, and AI resides in the mouths of people marketing stuff that while initially impressive has demonstrated more and more that it can regurgitate the opinions of others based on what it has read. This marketers have celebrated as a success, and this I have seen as a limitation that more data is not going to solve.

‘Spheres of Influence’ also… aren’t spheres. They are shaped by what we are exposed to, and when people focus on one aspect I describe it as wobbling, because these ‘spheres’ spin, and it’s convenient to talk about spheres since they are so perfect – but we are not perfect, we have our biases, some of us delve deeply into subjects and change our centers drastically. People who are more open minded would be more fluid, like water, and those who are closed minded can be like concrete.

It’s something to consider when we assess intelligence, consciousness, or our own lives – and what we’re being sold, or what we’re being told should be important to us.

This kind of stuff is part of the basis of the novel I’ve been working on. Would love to hear more from others, though my own sphere of influence on the internet is not that large. Comment below.

- Her book comes out in August 2024, and I’ll get a copy because of how she expressed what she did: “Life as No One Knows It: The Physics of Life’s Emergence”. I didn’t agree with everything she said, and that’s exactly why she’s worth reading for me. I may not know enough. 🙂 ↩︎

- I prefer the Spanish word idioma for language – it seems much more sensible to me as it encapsulates dialects as well. ↩︎

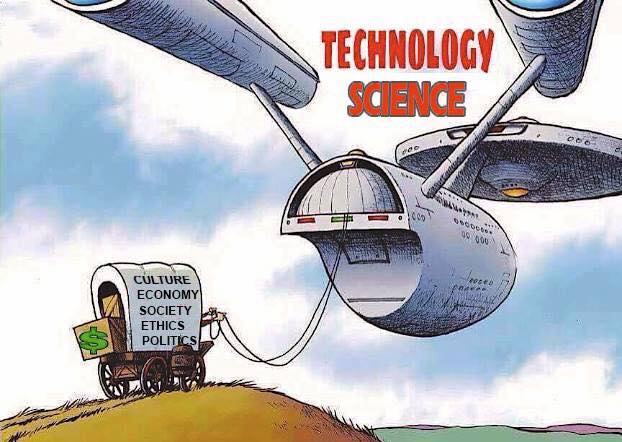

It’s not something new for me to write about – in fact, most of my writing has centered around the constant conflict I feel between technology and… well, just about everything else. I am, at heart, a technology person. By no stretch am I a Luddite, as a Beowulf cluster of Pine64s a few feet away shows.

It’s not something new for me to write about – in fact, most of my writing has centered around the constant conflict I feel between technology and… well, just about everything else. I am, at heart, a technology person. By no stretch am I a Luddite, as a Beowulf cluster of Pine64s a few feet away shows.