Reading Last Days by ThatNursePatty reminded me of something. My medical experience as a Hospital Corpsman was largely emergency medicine, and I rarely got to follow up on patients we admitted. I tried because it’s good to get feedback from the wards, such as why they hated our antecubital IVs.

It was an overcast day as I pulled into the apartment complex in New Smyrna Beach when in the middle of the roadway a woman flagged me down, a phone in one hand, tears streaming down her face. I pulled over and got out.

She was someone I had not seen before, and she was screaming at a million miles an hour. Following the general direction where she was waving I found an elderly man laying on the ground, and remembering my old days as a Navy Corpsman, I did a quick assessment. He was unresponsive.

There was a pool of blood on the ground below his head and I could not get an answer from the screaming woman how he had gotten on the ground. I told her in the calmest voice I could she needed to call 911 and get an ambulance there, but she was… not listening, screaming instead, and finally I projected my voice and got her attention.

She called, and promptly started screaming into the phone at the poor 911 person, and I could hear it going nowhere.

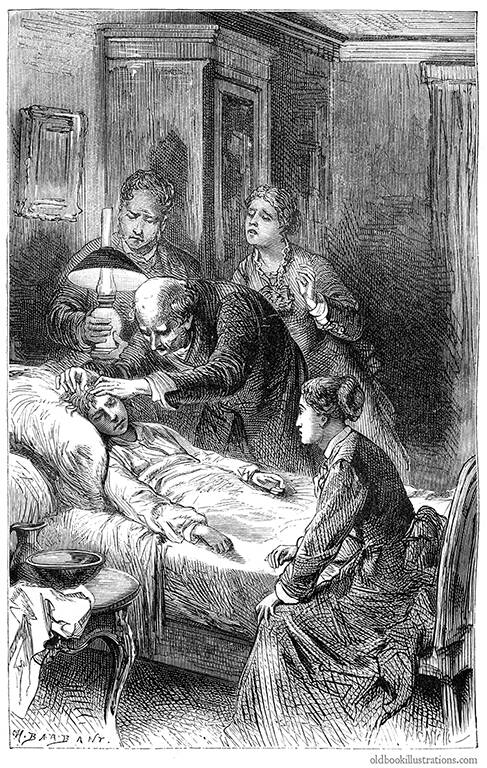

My assessment of what I now knew was her father was a possible C-Spine injury, eyes not equal or reacting to light, and a really thready pulse with low respirations and decreasing. I was holding a rag I had grabbed from my car against the back of his head, where the wound was. The blood on the ground wasn’t clotting, he’d lost at least a pint on the asphalt before I got there and it wasn’t coagulating. I suspected he was on blood thinners. CPR wasn’t called for at this time, so I just maintained his C-spine while keeping my fingers on his carotid so I could keep track of his pulse.

I got her to come over and place the phone on my shoulder so I could talk to the 911 operator. I fell back easily into ER talk, giving the operator a rundown which she couldn’t understand. She couldn’t connect me to the ambulance. She couldn’t connect me to an ER to talk to a doctor. I knew this old man didn’t have the 15 minutes she said it would take for the ambulance to get there.

She was back in the middle of the road screaming her dismay at the Universe, and her father was not likely to last that long. His pulse became increasingly thready, his respirations became slower and more relaxed, and I called her over to hold his hand and talk to him. She was, unfortunately, not done with the Universe, and still had much to say to the Universe. He was slipping away.

I spoke to him quietly,focused on him, and I waited while counting his respirations, feeling his pulse slip away, managing his head wound as best I could while keeping his neck in line.

The ambulance eventually arrived, and I did my handoff to the paramedics. He was pretty much gone, his pulse still faintly there, shallow respirations down to about 4 a minute. I gave one paramedic the look, he nodded curtly and quietly, and I got up and walked to my car and drove off to my parking spot for my apartment.

I would find out that he didn’t make it, as I expected. Too much time had been lost. His daughter would end up finding me the next day and thanking me for helping, breaking down into tears. She had been so wrapped up in herself she had not spent the time with him when she could have, but that was not for me to tell her. It wasn’t even necessarily right for me to tell her.

In the moment, people react to emergencies in different ways. Not everyone is trained for them. Not everyone is good at them. And when it’s a person we care about we become compromised, some more than others, but we all become compromised in one way or the other.

I don’t know what happened to her. I saw her off and on over the course of a few months. She kept to herself, possibly reliving that time herself in dark moments. Did she have regrets? Would she have them? I do not know.

It wasn’t the first time I’d seen such a thing, and it wouldn’t be the last. People thought highly of me in that complex afterward.

I hadn’t saved his life. I hadn’t even made it better for the short time we were in contact. Hopefully he was a little more comfortable. In the end, that’s what we can do on the worst day:

Make someone a little more comfortable.

It was planned, this surgery, and while the particulars aren’t important, I found the process worth writing about. After all, people poking about in one’s body has become remarkably commonplace in the last century.

It was planned, this surgery, and while the particulars aren’t important, I found the process worth writing about. After all, people poking about in one’s body has become remarkably commonplace in the last century.