If I tell you that all apples sound the same, these days you might think I was talking about an overpriced consumer electronics device.

Maybe I am, maybe I’m not. If I were referring to the brand, if you’re a consumer of that brand you might feel attacked and want to defend your choices because I used the word ‘overpriced’. If you’re not a consumer of that brand you might smile quietly at the description.

If I instead said “All red apples sound the same”, you might lean toward fruit because the Apple brand is not particularly red. In fact, they market as silver.1

It’s a pretty silly statement otherwise, we might think. Different colors of apples do not have different sounds that we hear. Yet it’s also a very true statement for the same reason.

Color is something we agreed upon despite how many types of color receptors you have in your eyes. 2 We may not experience the color the same in our minds, yet we all agree that things that reflect certain parts of light are indeed ‘red’.

In fact I can say that apples aren’t red. We all agree that they look red to us, but what they look like isn’t what they are. They happen to look like that because we happen to have organs that interpret vibrations of light waves into our little reality in our heads that allows us to bounce our shins just enough to remember how painful it is to bounce your shins.

But sound? Vibration and frequency, except sound requires a medium to go through and light does not.

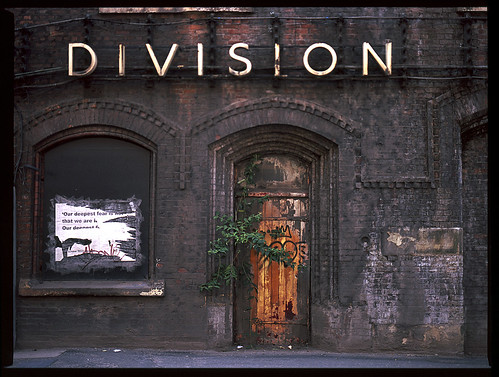

We are all just building our own little worlds. Language allows us to share our worlds.

- As silver as an Apple. Knowing Apple, there’s a specific shade of silver and they have a name for it. ↩︎

- There’s an online ‘test’ that has been popular recently where everyone thinks they’re a tetrochromate, but that test is questionable. ↩︎