There’s a world out there.

I’m not writing about the world we all agree to, the things we take for granted and don’t question, even down to social graces and traditions.

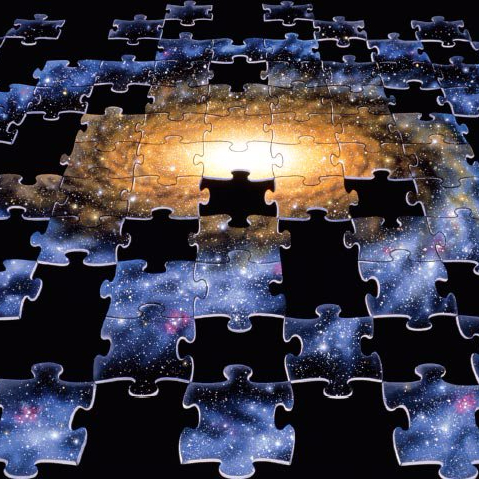

There’s a world out there beyond what you see, what I see, what we all see. If you have a moment, it’s thoroughly interesting.

Our minds have this way of taking shortcuts. It’s the way we have managed to survive dangerous creatures and even social situations. Being afraid of snakes, spiders, heights, etc. – those are survival traits. If you’re not afraid of them you better be good at killing them quickly, using that adrenaline to fight instead of run. Survival of surviving a battle with a dangerous creature is likely not as high as running away, in general.

Beyond our reflexive responses lays a level of interaction that allows us to change the responses. I was afraid of snakes, so I raised some and got to know them and also myself just a little bit better. Spiders I wasn’t afraid of, but heights, sure. So I jumped off of things, out of things, etc. When you understand how much time you feel you have on the way down, you’re free of everything for a relatively short time.

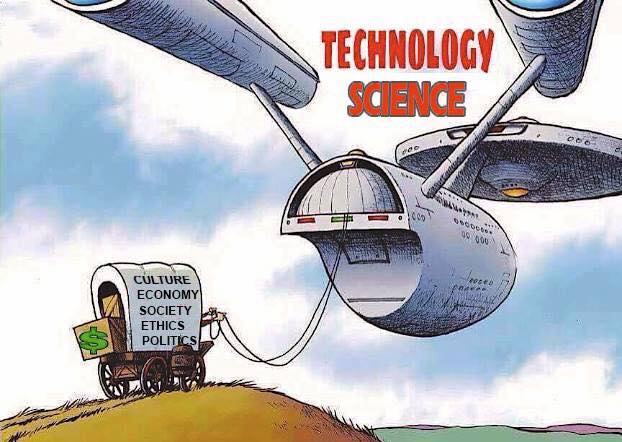

If the reality we see is real, when it gets challenged it shouldn’t change. So what shaped the reality? What you shove into your sensors and brain, or what was shoved in. We who would deign to train AIs to be better than us are as flawed as our sense of reality, and that sense is so fragile that when others don’t share our sense of reality we discard them rather than explore them. We may even mock them, all the while wondering how dumb the other person is to not see things the way we do. Or how their personality is flawed. Or how they’re too ‘woke’ or ‘unwoke’.

To be fair, that last one seems fair criticism both ways most of the time. I identify as a social critic. Bite me.

When we have polarized disagreements, nothing good happens. Being ‘right’ doesn’t change things, it just makes you look like you have the power of foresight. Understanding why other people think they are ‘right’ is key to us understanding ourselves and coming to a reality we can all agree on. It is easy to write but almost impossible to happen.

Instead, people shout at each other because of the mob around them that gives them comfort and the illusion of safety. It becomes about dominance, and when it’s a battle for dominance expect blood. The world we have built, this reality, doesn’t tolerate the perception of weakness. It’s as unforgiving as we are, which is no mistake. That is, for better or worse, who we are. At least now.

It doesn’t have to be who we are, but we collectively chose this way for quite some time. Most of it probably started long ago, before the different religions that showed up all claiming that they were all right. We created Gods who are as vengeful as we are, largely written by men who decided that writing and dressing funny was more important than pleasurable procreation. Those guys had to be miserable. And because they were miserable, they made other guys like them copy them.

They had good days though, taking poetic license with what could be encapsulated in a 5 word sentence: “Be nice to each other.” On the bad days things were smitten, burned, or otherwise destroyed. On the good days, seas were parted. On the bad days, there were floods. I could do other references, but those are pretty well known across this human society – it’s woven into our reality, even if we’re not that religion. Few question it. Most go along with it. It’s easier that way. We like doing things that are easy. To defy a commonly agreed upon reality is a dangerous thing to do.

Thinking beyond the box is heresy to some, but the only box there is what some other people agreed to propagate. It’s the box agreed upon implicitly, unconsciously, and it does not always suit us well.