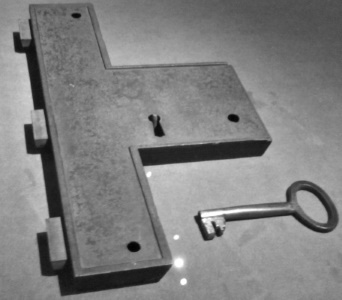

As a member of the Board for what could best be explained as a condo community, I find myself shaking my head quite a bit. One of the reasons I do so is because, simply put, people become more emotionally attached to a problem than a solution. One such example was an issue of a missing key. But the issue wasn’t the missing key. The issue was getting to what the key gave access to: The garbage room.

As a member of the Board for what could best be explained as a condo community, I find myself shaking my head quite a bit. One of the reasons I do so is because, simply put, people become more emotionally attached to a problem than a solution. One such example was an issue of a missing key. But the issue wasn’t the missing key. The issue was getting to what the key gave access to: The garbage room.

There’s a story behind that, as there usually is, but at this point in time there’s actually little good reason for the garbage room to be locked. At one time, there was some rationale, but that rationale has been found wanting as other things have changed. I had predicted this prior to coming on the Board, communicated it with the Director who pushed it (who is now no longer on the Board), and so I waited over the course of a week as this can got kicked around in community chats.

The conversation centered around the key. The key became this Holy Grail of sorts, and everyone wanted to blame someone for the issue regarding the key (it is lost to the entropy of bureaucracy, suffice to say). After a week, I finally sounded off because the time it was taking for people to sort out the problem had exceeded my patience.

“We don’t need the locks on the garbage rooms anymore.”

The underlying issue was that people couldn’t access the garbage room for bags that were larger than the chute. Everyone wanted to play the blame game about the key, and meanwhile, the garbage room was still inaccessible. And this set me to thinking because when large groups of fairly intelligent people disappoint in their capacity to solve a simple problem, it’s time to think.

The Solving Of Problems

There is a tendency to get caught up in minutiae, trying to solve a smaller problem with an assumption that solving the smaller problem will somehow continue solving a larger problem. In the above example, it was a simple matter of switching perspectives, a flexibility in viewpoint to be circumspect. Generally speaking, education systems, perhaps because of the amount of time to shove a few thousand years of knowledge into less than 20 years, doesn’t deal with this well.

Let’s be honest, too – the present techno-communication landscape of social media is more suited for allowing for cognitive bias: Social media sites, in their wish to get our eyes on their advertising, show us what we agree with rather than well rounded opinions. It’s all an echo chamber and makes looking for valuable dissent (as opposed to popular dissent) all the less likely to be found.

If we are only presented that which we agree with, how are we to move forward? If a solution is chosen because of popularity on social media, how valuable is that solution? And do all these people with opinions have knowledge on the topic or add value somehow, or are they simply looking for views on their website, just as without social media sometimes people add their opinions to look smart even when their opinion demonstrates that they are not?

It seems to me – and we all have biases on this – that the world is getting better at communicating solutions that are popular, but not right – and therein, we find the core problem, and the solution is… well, I’m sure I don’t know.