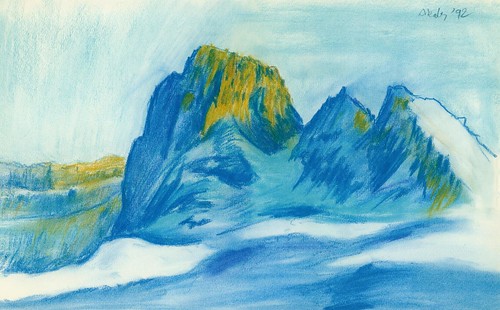

People do amazing things with simple items. Take crayons, for example.

The image at top was done with what we consider children’s tools. We send them off to color between the lines in the hope that they’ll be quiet. Maybe hoping that their hand-eye coordination improves as they grow older so that they can stay within the lines – and society likes things that stay in lines. That follows something someone else drew. Whose vision is limited to what is possible within those lines.

It keeps things safe. Predictable. Unambiguous.

It keeps things safe. Predictable. Unambiguous.

Yet we celebrate those who can do things without lines that we can identify with – we like art we can identify with. With lines. With a framework. A framework we can identify.

Stray too far, and it makes people uncomfortable. Few people like uncomfortable.

People want order. Nice lines of what can be expected.

Everything in it’s place.

Everything explained, even if by a theory incomplete.

The trouble is that we just get the same things when we do the same things. There might be some variance, but it’s the accepted range of things.

The only real moves forward humans have made have been when people color outside the lines.

The only real moves forward humans have made have been when people color outside the lines.

When the crayons are outside of the box, the framework.

When they’re disorganized.

Mixed up.

When the canvas is clear of lines we thought we needed.

A mess of crayons and a blank page is how we let children play.

When did we lose that?

Or do we still have it?