Reuters Institute posted a thread on Twitter regarding how news sites in the United States reacted to the General Protection Regulation (GDPR), as well as the fallout. It’s an interesting thread, but the article linked to is actually quite thought provoking.

Reuters Institute posted a thread on Twitter regarding how news sites in the United States reacted to the General Protection Regulation (GDPR), as well as the fallout. It’s an interesting thread, but the article linked to is actually quite thought provoking.

…One publication, USA Today, rationed EU users’ access, redirecting them to a GDPR-compliant bare-bones version of their site. Other US news sites, like The New York Times, immediately adapted to the GDPR and didn’t block. Although some of the hundreds of US sites that blocked remain blocked to this day, others, like the Los Angeles Times, restored full access after a number of months, and others after a number of years.

The differing strategies of these news sites allowed us to conduct a quasi-experimental study on the effects on consumption of temporary website withdrawal and temporary rationing…

This holds interests for other reasons, which I’ll get to later. What they found was:

…In conclusion, our study supports the theory that, under particular conditions, unavailability can reduce a product’s desirability, affecting future choices. Sour grapes, in this instance, had the upper hand…

So this demonstrates how making something exclusive doesn’t always make it more sought after.

The full study, “Forbidden fruit or soured grapes? Long-term effects of the temporary unavailability and rationing of US news websites on their consumption from the European Union“, is also worth a read if you want to get into the details – as I think you should.

The reason I brought this up is that we often consider site technical issues or business decisions as something that impacts whether a site’s content is seen. It has a latency issue after correction, it ends up, and while there’s not enough information from the study, it does seem the proportionality of return to use is proportional to to how long the content was unavailable. There are two issues I’ll bring up, the first being…

Paywalls.

I take issue with paywalls.

Don’t get me wrong, I believe in writers getting paid, and I would like to get paid sometime for writing. I subscribe to a Iona Italia on substack and Unherd.com presently, and have been toying with going back to subscribing to Scientific American. I’m tough when it comes to subscriptions. I subscribe to Iona because I think reading her can make me a better writer – and while the same is true for Unherd.com, I enjoy the articles because they’re not just run of the mill, even those I find issues with. It’s original.

However, today I saw an interesting article on Twitter by Harvard Business Review (HBR), which dutifully distracted me by pointing out it was my last ‘free’ article for the month as some sites do. They have been getting me to click, according to the HBR article limits at present, 4 times this month and it’s the 19th.

I thought about it. I couldn’t recall the other articles I read on HBR. Still, what’s the cost, then?

$12.50 US a month.

So for 4 articles in 19 days, that would put me at 6.3 articles in 30, which comes up to $1.98 an article for me. I’m sorry, HBR, I just don’t see spending $2/article, when an article might take me 7 minutes to read. Now, this is not to say HBR doesn’t have good articles, but how often are they interesting enough for me?

Short answer: not enough for me to subscribe.

Does that mean I’m unwilling to pay HBR for articles? No. It means I don’t want to pay their monthly price because I can’t depend on them to be interesting to me every month. This was the problem with magazine subscriptions I had (and why I’m still debating renewing my ancient Scientific American subscription), whereas with Unherd.com I spent around $49/year, and while I’m not reading them every day, I peruse the site at least 3 times a week, reading at least12 articles a month. Quick math, dropping a dollar off the annual subscription gives us $48/year, which comes up to $4/month, where I’m reading 12 articles in a month and paying… $0.33/article.

More importantly, given it takes me the same amount of time to read an article on HBR as Unherd, I’m getting more time reading for the price. Now, this is unfair. HBR is a niche market and few of their articles would appeal to me – but the few that do, I might pay for, but I’m not going to pay more than I do for a can of Coke for something that lasts me 7 minutes. I’m a reader, not some client visiting a hooker.

New York Times does this, as do a few other sites, and each time I go through a similar process. I call it ‘signal to noise’ because for me, that’s what it is. I get better signal to noise with Unherd than I do with HBR, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want the signal from HBR. I’m just not willing to pay for what I consider noise. Attenuate, attenuate!

So in my mind, people are leaving dollars on the table. I might start an account for $10 and pay 33.3 cents an article, and replenish the account if I get value for it. If I’m reading enough, the subscription price might be a deal.

This all lead me back to the days when I sat with Phil Hughes in Nicaragua and discussed revenue for print publications with him, then publisher of Linux Journal. He of course had a lot more experience than I, and he told me why print and web advertising were such different beasts – it has to do with verifiable views, which at the time were easily gamed by simply refreshing the pages. Now they can be gamed by bot farms, so the cost of web advertising began low and has credible reason not to increase except for one major thing: User accounts, which the newspapers and magazines have unimaginatively done without considering the money they’re leaving on the table.

Why am I so concerned? My real issue with paywalls is that they keep me from accessing information, or knowledge, and that affects how I make decisions – just as it affects how you make decisions. When you cut out segments of society and create silos of information, the Internet simply is repeating the same thing that print publications do except… you can’t let me read your magazine when you’re done, and I can’t do the same. There was a time when people would find valuable things in old magazines laying around.

So what happens when I see that I’m out of articles on a site? I roll my eyes, move on with my life and ignore links to the site for an indeterminate period, much like the Reuters Institute paper shows. It could be a month, it could be 2 months… and I’ll simply forget I have ‘free’ articles to read.

Yet even with that, I have the luxury of spending 33 cents on an article. Some people don’t. Some people may not even have access to a credit card in some countries, and just like that, the digital divide becomes an informational divide. The only real answer in my mind is to increase advertising costs to cover that of the writers, the editors, and the boss’s nephew manning the photocopier and fax in the basement.

Derivative Knowledge

Now, all of this impacts something else.

It impacts AIs being trained on the Internet, who are unlikely to see paid content and thus are stuck reading free websites. That seems stupid, but in the house of cards of business, maybe there’s an upside to having an AI trained without subscriptions. I just don’t know what it is.

There was a time when I thought all information should be free. There was even a stab at a Creative Commons license for developing nations, which would have been more equitable and allowed those who could afford to carry the cost for those trying to catch up. This could also work for AIs being trained, but, with the popularity of VPNs as they are, information accessibility in developed nations could easily be subverted by simply using a VPN server in Haiti, as an example.

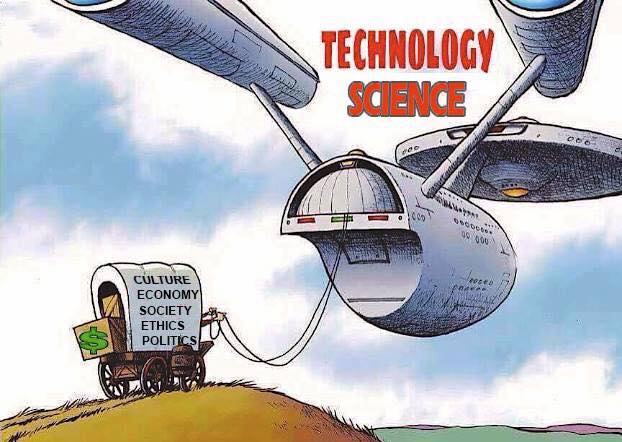

And all of this leads up to derivative knowledge, because that impacts decision making – not just of machines, but that of people.

If the media industry on the Internet wants to actually be read and interacted with… understanding these things better makes sense. Or, that latency of not visiting could catch up, or… we could just leave a bunch of people behind because we couldn’t find a better solution.